Lapse rate

The lapse rate is defined as the rate of decrease with height for an atmospheric variable. The variable involved is temperature unless specified otherwise.[1][2] The terminology arises from the word lapse in the sense of a decrease or decline; thus, the lapse rate is the rate of decrease with height and not simply the rate of change. While most often applied to Earth's atmosphere the concept can be extended to any gravitationally supported ball of gas.

Contents |

Definition

A formal definition from the Glossary of Meteorology[3] is:

- The decrease of an atmospheric variable with height, the variable being temperature unless otherwise specified.

- The term applies ambiguously to the environmental lapse rate and the process lapse rate, and the meaning must often be ascertained from the context.

The atmospheric lapse rate describes the reduction, or lapse of air temperature that takes place with increasing altitude. Lapse rates related to changes in altitude can also be developed for other properties of the atmosphere.

In the lower regions of the atmosphere (up to altitudes of approximately 40,000 feet [12,000 m]), temperature decreases with altitude at a fairly uniform rate. Because the atmosphere is warmed by conduction from Earth's surface, this lapse or reduction in temperature normal with increasing distance from the conductive source.

Although the actual atmospheric lapse rate varies, under normal atmospheric conditions the average atmospheric lapse rate results in a temperature decrease of 3.5°F (1.94°C) per 1,000 feet (304 m) of altitude.

The measurable lapse rate is affected by the moisture content of the air (humidity). A dry lapse rate of 5.5°F (3.05°C) per 1,000 feet (304 m) is often used to calculate temperature changes in air not at 100% relative humidity. A wet lapse rate of 3°F (1.66°C) per 1,000 feet (304 m) is used to calculate the temperature changes in air that is saturated (i.e., air at 100% relative humidity). Although actual lapse rates do not strictly follow these guidelines, they present a model sufficiently accurate to predict temperate changes associated with updrafts and downdrafts. This differential lapse rate (dependent upon both difference in conductive heating and adiabatic expansion and compression) results in the formation of warm downslope winds (e.g., Chinook winds, Santa Anna winds, etc.). The atmospheric lapse rate, combined with adiabatic cooling and heating of air related to the expansion and compression of atmospheric gases, present a unified model explaining the cooling of air as it moves aloft and the heating of air as it descends downslope.

Atmospheric stability can be measured in terms of lapse rate (i.e., the temperature differences associated with vertical movement of air). A high lapse rate indicates a greater than normal change of temperature associated with a change in altitude and is characteristic of an unstable atmosphere.

Although the atmospheric lapse rate (also known as the environmental lapse rate) is most often used to characterize temperature changes, many properties (e.g., atmospheric pressure) can also be profiled by lapse rates.

See also Air masses and fronts; Land and sea breeze; Seasonal winds

Mathematical definition

In general, a lapse rate is the negative of the rate of temperature change with altitude change, thus:

where  is the lapse rate given in units of temperature divided by units of altitude, T = temperature, and z = altitude.

is the lapse rate given in units of temperature divided by units of altitude, T = temperature, and z = altitude.

Note: In some cases,  or

or  can be used to represent the adiabatic lapse rate in order to avoid confusion with other terms symbolized by

can be used to represent the adiabatic lapse rate in order to avoid confusion with other terms symbolized by  , such as the specific heat ratio[4] or the psychrometric constant.[5]

, such as the specific heat ratio[4] or the psychrometric constant.[5]

Types of lapse rates

There are two types of lapse rate:

- Environmental lapse rate – which refers to the actual change of temperature with altitude for the stationary atmosphere (i.e. the temperature gradient)

- The adiabatic lapse rates – which refer to the change in temperature of a parcel of air as it moves upwards (or downwards) without exchanging heat with its surroundings. The temperature change that occurs within the air parcel reflects the adjusting balance between potential energy and kinetic energy of the molecules of gas that comprise the moving air mass. There are two adiabatic rates:[6]

- Dry adiabatic lapse rate

- Moist (or saturated) adiabatic lapse rate

Environmental lapse rate

The environmental lapse rate (ELR), is the rate of decrease of temperature with altitude in the stationary atmosphere at a given time and location. As an average, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) defines an international standard atmosphere (ISA) with a temperature lapse rate of 6.49 K(°C)/1,000 m (3.56 °F or 1.98 K(°C)/1,000 Ft) from sea level to 11 km (36,090 ft). From 11 km (36,090 ft or 6.8 mi) up to 20 km (65,620 ft or 12.4 mi), the constant temperature is −56.5 °C (−69.7 °F), which is the lowest assumed temperature in the ISA. The standard atmosphere contains no moisture. Unlike the idealized ISA, the temperature of the actual atmosphere does not always fall at a uniform rate with height. For example, there can be an inversion layer in which the temperature increases with height.

Dry adiabatic lapse rate

The dry adiabatic lapse rate (DALR) is the rate of temperature decrease with height for a parcel of dry or unsaturated air rising under adiabatic conditions. Unsaturated air has less than 100% relative humidity; i.e. its actual temperature is higher than its dew point. The term adiabatic means that no heat transfer occurs into or out of the parcel. Air has low thermal conductivity, and the bodies of air involved are very large, so transfer of heat by conduction is negligibly small.

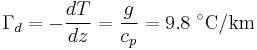

Under these conditions when the air rises (for instance, by convection) it expands, because the pressure is lower at higher altitudes. As the air parcel expands, it pushes on the air around it, doing work (thermodynamics). Since the parcel does work but gains no heat, it loses internal energy so that its temperature decreases. The rate of temperature decrease is 9.8 °C per 1,000 m (5.38 °F per 1,000 ft) (3.0°C/1,000 ft). The reverse occurs for a sinking parcel of air.[7]

Since for adiabatic process:

the first law of thermodynamics can be written as

Also since : and :

and : we can show that:

we can show that:

where  is the specific heat at constant pressure and

is the specific heat at constant pressure and  is the specific volume.

is the specific volume.

Assuming an atmosphere in hydrostatic equilibrium:[8]

where g is the standard gravity and  is the density. Combining these two equations to eliminate the pressure, one arrives at the result for the DALR,[9]

is the density. Combining these two equations to eliminate the pressure, one arrives at the result for the DALR,[9]

.

.

Saturated adiabatic lapse rate

When the air is saturated with water vapor (at its dew point), the moist adiabatic lapse rate (MALR) or saturated adiabatic lapse rate (SALR) applies. This lapse rate varies strongly with temperature. A typical value is around 5 °C/km (2.7 °F/1,000 ft) (1.5°C/1,000 ft).

The reason for the difference between the dry and moist adiabatic lapse rate values is that latent heat is released when water condenses, thus decreasing the rate of temperature drop as altitude increases. This heat release process is an important source of energy in the development of thunderstorms. An unsaturated parcel of air of given temperature, altitude and moisture content below that of the corresponding dewpoint cools at the dry adiabatic lapse rate as altitude increases until the dewpoint line for the given moisture content is intersected. As the water vapor then starts condensing the air parcel subsequently cools at the slower moist adiabatic lapse rate if the altitude increases further.

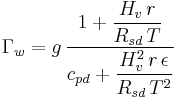

The saturated adiabatic lapse rate is given approximately by this equation from the glossary of the American Meteorology Society:[10]

-

where:

= Wet adiabatic lapse rate, K/m

= Earth's gravitational acceleration = 9.8076 m/s2

= Heat of vaporization of water, J/kg

= The ratio of the mass of water vapor to the mass of dry air, kg/kg

= The universal gas constant = 8,314 J kmol−1 K−1

= The molecular weight of any specific gas, kg/kmol = 28.964 for dry air and 18.015 for water vapor

= The specific gas constant of a gas, denoted as

= Specific gas constant of dry air = 287 J kg−1 K−1

= Specific gas constant of water vapor = 462 J kg−1 K−1

=The dimensionless ratio of the specific gas constant of dry air to the specific gas constant for water vapor = 0.6220

= Temperature of the saturated air, K

= The specific heat of dry air at constant pressure, J kg−1 K−1

Significance in meteorology

The varying environmental lapse rates throughout the Earth's atmosphere are of critical importance in meteorology, particularly within the troposphere. They are used to determine if the parcel of rising air will rise high enough for its water to condense to form clouds, and, having formed clouds, whether the air will continue to rise and form bigger shower clouds, and whether these clouds will get even bigger and form cumulonimbus clouds (thunder clouds).

As unsaturated air rises, its temperature drops at the dry adiabatic rate. The dew point also drops (as a result of decreasing air pressure) but much more slowly, typically about −2 °C per 1,000 m. If unsaturated air rises far enough, eventually its temperature will reach its dew point, and condensation will begin to form. This altitude is known as the lifting condensation level (LCL) when mechanical lift is present and the convective condensation level (CCL) absent mechanical lift, in which case, the parcel must be heated from below to its convective temperature. The cloud base will be somewhere within the layer bounded by these parameters.

The difference between the dry adiabatic lapse rate and the rate at which the dew point drops is around 8 °C per 1,000 m. Given a difference in temperature and dew point readings on the ground, one can easily find the LCL by multiplying the difference by 125 m/°C.

If the environmental lapse rate is less than the moist adiabatic lapse rate, the air is absolutely stable — rising air will cool faster than the surrounding air and lose buoyancy. This often happens in the early morning, when the air near the ground has cooled overnight. Cloud formation in stable air is unlikely.

If the environmental lapse rate is between the moist and dry adiabatic lapse rates, the air is conditionally unstable — an unsaturated parcel of air does not have sufficient buoyancy to rise to the LCL or CCL, and it is stable to weak vertical displacements in either direction. If the parcel is saturated it is unstable and will rise to the LCL or CCL, and either be halted due to an inversion layer of convective inhibition, or if lifting continues, deep, moist convection (DMC) may ensue, as a parcel rises to the level of free convection (LFC), after which it enters the free convective layer (FCL) and usually rises to the equilibrium level (EL).

If the environmental lapse rate is larger than the dry adiabatic lapse rate, it has a superadiabatic lapse rate, the air is absolutely unstable — a parcel of air will gain buoyancy as it rises both below and above the lifting condensation level or convective condensation level. This often happens in the afternoon over many land masses. In these conditions, the likelihood of cumulus clouds, showers or even thunderstorms is increased.

Meteorologists use radiosondes to measure the environmental lapse rate and compare it to the predicted adiabatic lapse rate to forecast the likelihood that air will rise. Charts of the environmental lapse rate are known as thermodynamic diagrams, examples of which include Skew-T log-P diagrams and tephigrams. (See also Thermals).

The difference in moist adiabatic lapse rate and the dry rate is the cause of foehn wind phenomenon (also known as "Chinook winds" in parts of North America).

See also

References

- ^ Mark Zachary Jacobson (2005). Fundamentals of Atmospheric Modeling (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83970-X.

- ^ C. Donald Ahrens (2006). Meteorology Today (8th ed.). Brooks/Cole Publishing. ISBN 0-495-01162-2.

- ^ Todd S. Glickman (June 2000). Glossary of Meteorology (2nd ed.). American Meteorological Society, Boston. ISBN 1-878220-34-9. (Glossary of Meteorology)

- ^ Salomons, Erik M. (2001). Computational Atmospheric Acoustics (1st ed.). Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 1-4020-0390-0.

- ^ Stull, Roland B. (2001). An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology (1st ed.). Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-277-2769-4.

- ^ Adiabatic Lapse Rate, IUPAC Goldbook

- ^ Danielson, Levin, and Abrams, Meteorology, McGraw Hill, 2003

- ^ Landau and Lifshitz, Fluid Mechanics, Pergamon, 1979

- ^ Kittel and Kroemer, Thermal Physics, Freeman, 1980; chapter 6, problem 11

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology

Additional reading

- Beychok, Milton R. (2005). Fundamentals Of Stack Gas Dispersion (4th ed.). author-published. ISBN 0-9644588-0-2. www.air-dispersion.com

- R. R. Rogers and M. K. Yau (1989). Short Course in Cloud Physics (3rd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3215-1.

External links

- Definition, equations and tables of lapse rate from the Planetary Data system.

- National Science Digital Library glossary:

- An introduction to lapse rate calculation from first principles from U. Texas

|

|||||||||||||||||